BLOG

Go Make Something Embarrassing

Don’t be so afraid of making embarrassing work that you never make great work. (5 min read)

“If you’re not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you have launched too late.” (Reid Hoffman). This is one of my all-time favourite mantras to instill in the entrepreneurs I work with. Don’t wait until it’s perfect, even though that feels safer. Don’t wait until you have all the answers and your idea is polished and pretty. Don’t wait until you feel ready. Launch before; way before all that. Run quick, cheap experiments to test your hypotheses and keep iterating. It might feel all kinds of uncomfortable, but it’s the best way to make sure you’re actually building something people want.

Well, this autumn (2020) I’ve been walking my talk.

I’ve worked with people 1:1 for a long time, but for a while now I’ve been chewing on the idea of expanding to small groups. I spent the summer conducting research interviews with purpose-driven people in transition, learning what their main challenges were, and what they’d find most helpful in terms of support.

And across the board, they told me: “a group coaching programme”.

My interviewees were proactive and committed people who cared deeply about contributing to the greater good, but didn’t know how to move forward. They felt overwhelmed by too many options, held back by self-doubt, lost and isolated in the middle of all their questioning. They’d tried to think themselves out of this, but they’d just become more paralysed.

They knew that continuing to think about their transition wouldn’t work. They wanted a live programme, working alongside others, with professional support. Income was uncertain and money was tight, so a lengthy package of 1:1 work would feel tricky right now. But to work in a small group alongside me? They’d love it!

Great, I thought. I’d learned what they wanted.

But there was only one snag. I didn’t know how to go about delivering it.

While I’d run lots of workshops and facilitated many events, I’d never yet worked with this kind of format.

And so my first instinct was to go away and build it in private. Behind the scenes, I’d map out what I thought would be helpful, do lots of research, create modules and exercises, then present it as a ready-made solution.

And the best part? Even if not a single soul bought it or was helped by it, nobody would ever know!

It was low-risk and low-visibility. I loved it.

Then I remembered Reid’s advice.

Did I care more about showing up as professional and put-together, or about serving my people?

Paul Graham writes:

“One of the biggest things holding people back from doing great work is the fear of making something lame. And this fear is not an irrational one. Many great projects go through a stage early on where they don't seem very impressive, even to their creators. You have to push through this stage to reach the great work that lies beyond. But many people don't. Most people don't even reach the stage of making something they're embarrassed by, let alone continue past it. They're too frightened even to start.”

I didn’t want to miss out on creating something great because I was afraid of making something embarrassing.

And so, for the sake of the people I want to serve, I’ve completely turned the tables. In September 2020 I launched the beta run of my group coaching programme. I advertised it as a prototype rather than a finished product, and invited beta testers to help me build it as I went: telling me what would be most helpful week by week, and giving me feedback as I went.

And how’s it been? I hear you ask.

Have I fallen flat on my face?

More times than I can imagine. I now have very scabby knees. It’s felt vulnerable, exposing, and messy.

Has it been risky?

Yes and no. It’s definitely felt emotionally risky. There are moments that I’ve found very uncomfortable. I’m someone who likes to have my bases covered, so I’m pushing myself to trust the process that I believe in for other people.

And despite my emotional risk, in reality the stakes are very low. I’m explicit that it’s a prototype. And so I attract people who find that exciting, who know I’m learning and want to help contribute at a budget-friendly price. I get to under-promise and over-deliver.

Have I shown up and served my people?

Heck yes. Far more than if I’d played it safe and small. I’m being courageous for the sake of others’ growth. This way, I actually help them get where they want to go, rather than assuming I know the way. And by publicly stepping out of my comfort zone, I give others permission to do the same.

Will I look back and be embarrassed at the first version of my launch?

Honestly, I’m already embarrassed! :) There are so many things that I’ll already do differently in my next prototype, which — at the time of writing — starts in January 2021. I’ve made lots of mistakes. That means I’m doing things right.

Have people got huge value anyway?

Absolutely! Sure, not everything has landed. Sometimes I try things that don’t work.

But there are huge benefits to the format, too. People get to design the programme so that it’s tailored to their exact challenges. They get to build relationships with other purpose-driven people around the world (and get access to their network). They get to work with me at a lower price point than our 1:1 work. They’re getting real-life results — even though it’s the first time I’ve done it.

As Paul Graham continues: “Imagine how much more we’d do if we weren’t afraid of making something lame.”

I know that fear has held me back from launching all kinds of ideas in the past.

This time, I’m choosing not to listen.

Something to chew on: What’s something you’ve been sitting on for a while, hesitating to actually put out in the world? What’s one cheap and easy experiment you can take to make it just a bit more real?

A Purpose-Driven Case Study: Product-Market Fit

Here’s a high-level overview of how one group found a Product-Market Fit for their climate startup idea. (6 min read)

ⓒ Euro-Peeing Team, Climate-KIC Journey 2018. Used with permission.

Elsewhere I’ve written about how important it is for purpose-driven entrepreneurs, in particular, to focus on finding a Product-Market Fit. In other words, creating a product/service that actually meets the needs of your prospective customers or users. So, let’s make this a bit more tangible by diving into a case study from my own experience.

At The Journey, the world’s biggest climate change summer school for graduates and young professionals, I’ve coached 80 young people to develop business ideas that tackle environmental problems. (These ideas generally don’t go on to become start-ups, though some do. Instead, they’re practical exercises in how to think through how a climate start-up might be designed.)

We start The Journey by asking all participants to form small groups around climate problems they want to solve. Below, here’s how one group found their way to a Product-Market Fit.

A quick note before we jump in, though:

I’ll walk you through the process at quite a high level. In reality, this was far less clean-cut than this overview makes out: there were all kinds of discarded ideas, rabbit holes, difficult decisions, and pivot points that I’ve omitted for the sake of brevity. When you’re in the thick of this, it feels far more chaotic and a lot less linear!

All this happened in the space of just over two weeks. In the real world, of course, this would be a much more complex process. However, it does go to show what you can achieve in just sixteen days!

So: let’s get started. This is one of my favourite ideas that emerged from The Journey: Euro-Peeing.

Product-Market Fit: One Group’s Process

1. Targeting a climate problem

The group of four began by forming around their shared interest in a very broad climate problem: environmental damage caused by commercial fertilizer.

They began by researching this field to make sure they really understood their problem in context. For example: learning the most common ingredients used in commercial fertilizer, how these ingredients are sourced, main distribution networks, current techniques to apply fertilizer, main causes and effects of environmental damage, key stakeholders in the industry, etc.

2. Narrowing the focus area

The team decided to focus on a subset of this larger problem: nitrogen. Not only can nitrogen-based fertilizer be damaging to the ecosystem when it’s mismanaged, but the nitrogen itself depends partly on fossil fuels to be manufactured.

As a result, they chose to focus on the sourcing of this nitrogen in commercial fertilizer. They wondered if they could pioneer a more circular economy where nitrogen from an existing source could be used instead.

(Note: this ties into my previous post, where I write about how purpose-driven entrepreneurs generally work as part of a system, where lots of different interventions are needed to create large-scale change. For example, someone else might pioneer a less damaging method of applying the fertilizer; someone else might invent a fertilizer with different ingredients altogether. There are often lots of complementary ways to approach the same problem, some more impactful than others.)

3. Brainstorming

After brainstorming potential sources of existing nitrogen, the team chose one initial focus area: what if they could capture the nitrogen that occurs naturally in human urine, and repurpose it into fertilizer? This nitrogen is currently flushed away, it’s ubiquitous, and it’s free!

ⓒ Euro-Peeing Team, Climate-KIC Journey 2018. Used with permission.

4. Investigating

However, how might this translate into reality?

This was a very technical idea, so a lot of ground had to be covered to work out whether it was even doable.

For example, the group had to do a lot of research in terms of how to actually go about collecting the urine, and the various health and safety considerations that would need to be followed. They learned that the urine couldn’t be too diluted or mixed with anything else, so the regular sewage system couldn’t work. The urine would also need to be collected in large enough quantities that it was cost-efficient. What’s more: once this urine was captured, the nitrogen itself would need to be filtered out and sterilised before it could be converted into a state that was usable in fertilizer.

Lots of experts had to be consulted.

On paper, the team learned that the idea did seem feasible — at least for the purposes of their project.

5. Searching for a Product-Market Fit

The next parts of their process happened in tandem: weaving back and forth between learning about prospective customers’ problems, and brainstorming products that might address these.

Interviewing prospective customers

There was already a potential buyer: commercial fertilizer manufacturers who relied on nitrogen to make their product. But how about a supplier? In other words, was there a market that already relied on discarding undiluted urine in large quantities? And if so, how would they frame the biggest problems they faced?

The team began exploring the major stakeholders in sanitation, and interviewing people from these sectors. They learned that one big sanitation need was that faced by festival organisers in Europe. This industry already relies on chemical toilets to collect human waste from thousands of people in a short period of time, and it needs to dispose of this waste safely and as cheaply as possible.

So, what kind of solution did festivals currently look for? Based on interviews, the team learned that:

The sanitary solution needed to be cost-effective, easy-to-use, sanitary, and not smelly

It needed to be a full-service solution: hands-off for the festivals to install and maintain

It wasn’t crucial that it was eco-friendly (sanitation was more important), however:

Festivals were facing pressure from zero waste and environmental groups to minimise their waste and carbon footprint, so this was a nice-to-have if the above criteria were met

ⓒ Euro-Peeing Team, Climate-KIC Journey 2018. Used with permission.

Designing prototypes

As they learned more about the technology and their potential customers’ needs, the team designed a number of prototypes for portable toilets used at festivals. This would let them to collect a lot of undiluted urine in a short timeframe, while also addressing the festivals’ needs mentioned above.

While the team wanted to serve both sexes, their design process indicated that it was easier to focus just on males. That meant that their toilet became a urinal. This urinal attached to a portable storage and filtration system. All the infrastructure could be driven in and out of the festivals on trucks.

Festival organisers, when given briefs about the prototype, were positive. As long as these urinals were clean, affordable, and hands-off, they thought that the brand — emerging as ‘Euro-peeing’ — could be a great value-add for them in their own customers’ eyes, many of whom were climate-conscious and were demanding greener festival practices.

Interviewing all prospective customers and users

The team created a Business Model Canvas with two paying customers, and a non-paying user. For this model to work, all of these stakeholders would need to see the Euro-peeing product as solving a problem that they were experiencing.

Paying Customers:

Festival Organisers (who would rent the Euro-peeing urinals)

Fertilizer Manufacturers (who would buy the nitrogen gathered from the urine)

Users:

Male Festival-goers (who would urinate into the Euro-peeing urinal)

That meant that it wasn’t enough that the festival organisers were on board. The festival-goers needed to be, as well. What if they didn’t like the design of the Euro-peeing urine, or didn’t like the idea of their urine being used for fertilizer?

And what about the fertilizer manufacturers? Could the cost of this repurposed nitrogen compete with that of existing nitrogen sources? Were there any taboos that could make this unappealing to them?

The team needed to understand, and interview, these potential stakeholders, too.

ⓒ Euro-Peeing Team, Climate-KIC Journey 2018. Used with permission.

Iterating the prototype

The feedback from all these potential customers and users was key in shaping the design of the Euro-peeing urinal. The team also worked hard on ways to make the technology more cost-effective for both the festivals and the fertilizer manufacturers.

Once they had designed their prototype, the next step would be to manufacture a small number and supply them to a few European festivals as a beta run. This was a lower-cost way of testing some of their assumptions in the real world, and continuing to adjust the design while in conversation with their customers.

ⓒ Euro-Peeing Team, Climate-KIC Journey 2018. Used with permission.

Estimating market size

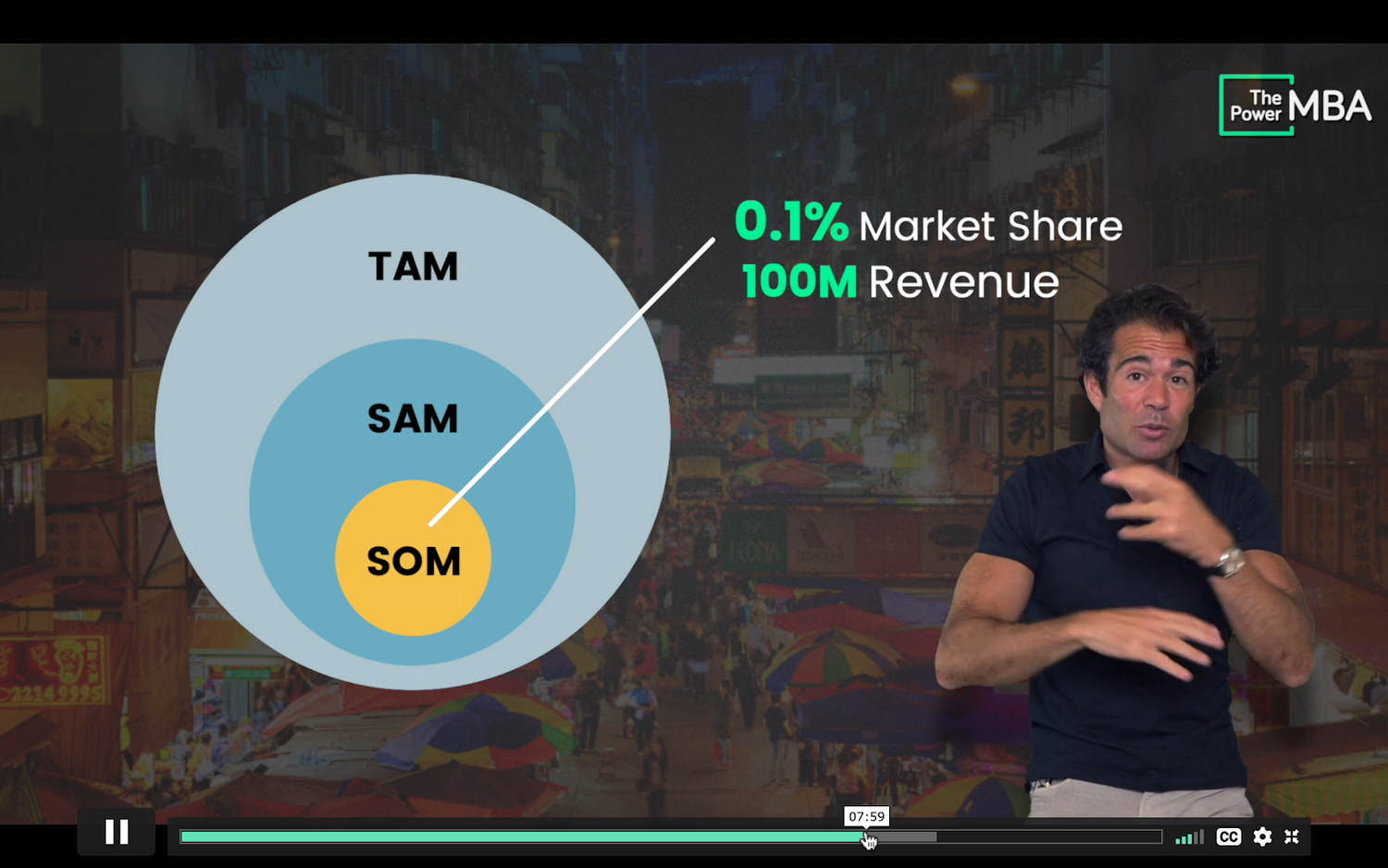

In The Journey, we didn’t advocate both the ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’ approaches to estimating market size (though now I’ve done ThePowerMBA, we will in future).

For the sake of illustration here, let’s run through a very high-level example, focusing solely on the portable toilet rental market (i.e., not the fertilizer market).

Top-down:

Taking the ‘top down’ approach, the team could start by researching the bigger picture, and then narrowing down to what was feasible for them.

For example, it might look like this:

The Total Addressable Market (TAM) = the value of the portable toilet rental market globally.

The Serviceable Addressable Market (SAM) = the value of that market portion taken up by European festivals.

The Serviceable Obtainable Market (SOM) = the % of festivals that the team could realistically convert as clients, given the team’s connections, distribution channels, existing competition, and available resources.

Bottom-up:

With the ‘bottom up’ approach, the team could look at some of their existing metrics and extrapolate upwards. For example, if they could have held sales calls with five festival organisers per week, and on average one in 10 of these converted to a client, how much of the market could they realistically capture at this stage?

The team could then combine the findings from both approaches, to give them a sense of what might be possible.

This, in turn, informed their estimation of their climate impact: how much CO2 they could potentially save through their solution.

ⓒ Euro-Peeing Team, Climate-KIC Journey 2018. Used with permission.

Key Takeaways:

The team’s Product-Market Fit wasn’t found instantly. It emerged over time, through repeated conversations with potential customers and users, ongoing research, and multiple iterations of the product. (Had it been taken forwards as an actual start-up, many more of the assumptions would need to have been tested in more robust ways.)

Even if it was a watertight business model on paper, and even if the urinal’s technology could solve an enormous environmental problem, that would all be irrelevant if nobody would use or rent their product. The idea alone wasn’t enough. They had to test, test, test, test, to find a Product-Market Fit, and create impact.

The Most Common Blindspots of Purpose-Led Entrepreneurs

Being purpose-led is a huge asset, but also a potential blindspot. (3 min read)

Finding a Product-Market Fit has been one of the main emphases in the first month of ThePowerMBA, the new business ed tech that’s revolutionising our access to business education. (I’ve written more about it here.)

A Product-Market Fit is about crafting a service/product designed to actually meet a need in the world. It sounds obvious. It sounds easy. But it’s often overlooked. And it’s especially important to know about if you’re a purpose-led entrepreneur.

Why?

Becauase if you’re purpose-led, you tend to be really passionate about a particular problem that you want to solve. Climate change. Animal welfare. Mental health. Toxic work cultures. These are the problems that keep you up at night, that you can’t imagine not wanting to contribute to somehow.

This passion is a tremendous asset. It will be your ‘WHY’: pulling you forward when things get tough, keeping you focused on the bigger purpose.

But as I’ve seen first-hand in my coaching work, this passion can also be a huge blind spot.

It can prevent you from actually creating something useful: something that somebody will truly want or use.

I’ve seen two blindspots in particular:

1. Your awareness of the problem (e.g., carbon emissions) can feel so urgent that you want to fix everything at once. It’s hard to narrow down to a particular contributor (e.g., within climate change) and decide to focus on that. It never feels like it will have enough impact, or happen fast enough. As a result, you struggle to identify a specific enough problem that you want to tackle.

2. At the other end of the spectrum, you can be so passionate about a very specific solution to a problem that you struggle to get truly objective about whether people actually want whatever you’ve dreamed up (e.g., whether they’ll use a behaviour change app aiming to reduce food waste and the associated carbon emissions). As a result, you don’t learn enough about how your customers think and act, and so your service/product (no matter how much you love it!) doesn’t really get off the ground.

In both cases, you never find a Product-Market Fit.

And as a result? You fail to make the difference you want to make.

Seeing The Product-Market Fit in Context

In our first month at ThePowerMBA, we’ve covered a huge amount of content, and I’m only focusing on a tiny part of it in this post. A central focus of what we’ve covered so far, however, has been the Business Model Canvas (BMC).

This was originally devised by Alex Osterwalder at Strategyzer, and is a beautifully intuitive tool aimed at capturing, on a single page, the key operating structure of any business.

On the Canvas, the Product-Market Fit is smack bang in the middle: straddling the space between your value proposition and your customer. When your value proposition exactly addresses something your customer is looking for, you have a Fit:

The Business Model Canvas, designed by Strategyzer AG, with my edits.

You start to look for your Fit through conducting quick and easy experiments, interviewing prospective customers, and testing your assumptions (a topic for a different post). While you do this, you’re also aiming to sketch out different business models, and explore them to see which one(s) might work best.

These are all things you don’t always know at the beginning, or that might change as you go along. As with so much in innovation, it’s an iterative process.

How Much Impact Could You Have?

As you’re exploring your Product-Market Fit, you’ll also need to reasonably estimate the potential size of that market. Again, this is especially important for purpose-driven changemakers, as the market size will cap your growth (and impact). Now, I know that not everyone wants to create something at scale with a lot of impact. However, if you do, this is really important to spend some time on.

There are two ways to estimate your market size, which ThePowerMBA takes you through.

One of them is ‘top down’: researching the total available market (Total Addressable Market: TAM). You then estimate the potential segment of it that you could realistically reach (Serviceable Available Market: SAM), then convert (Serviceable Obtainable Market: SOM).

The other is ‘bottom-up’: looking at your current data (e.g., hours currently spent on sales calls and the % of those calls that convert) and extrapolating your realistic market size from that.

Screenshot from ThePowerMBA, ‘Angles of Analysis: Market Sizing (& TAM SAM SOM.)

It’s best to cross-estimate your market size from both perspectives, to help you be as accurate as possible.

Key Takeaway

While being purpose-driven in business can be enormous asset, it can also blind you to the necessity of finding a Product-Market Fit. You might be so passionate about your (yet untested) solution, or so overwhelmed by the size of the problem, that you don’t create a service or product that specific customers will actually find helpful.

Make sure you take the time to truly understand your intended customers and the market potential for your idea. This will help you create as much impact, and make as much difference, as you can. After all, that’s why you’re trying to create something new in the first place, right? So let’s make it count!

Something to chew on: If you’re purpose-driven with a big idea, what blind spot do you need to be most aware of: overwhelm at the size of the problem, or over-attachment to your solution? What one action can you take to rebalance your approach?

(P.S. Want a practical case study to help make this real? Here’s a post that gives you just that!)

The Killer Antidote to Perfectionism

Aiming for perfection? That's what I tried when I began coaching. Then I discovered this - and it changed everything. (4 min read)

Elizabeth Gilbert once said that perfectionism is fear in high heels. Beneath the sexiness and shine of being a ‘high achiever’, it’s just plain old fear dressing itself up to look pretty.

When I started coaching in 2017, I was painfully aware of being brand new at all of this. I had just trained under some of the best coaches in the world. They’d shown me what mastery looked and felt like. And now here I was, fresh out of the gate, hanging up my shingle as a certified coach — all the while feeling like an utter fraud.

I longed for excellence.

I created a template that I filled out after each coaching session. One side listed the core competencies of my training school, which I’d grade myself on out of ten, looking back over the session. I imagined my instructors hovering over my shoulder, tutting and shaking their heads at this poor imitation of coaching. Flip over, and there was a grid with four boxes: what had gone well, what hadn’t gone so well, what I’d learned, and my takeaway actions to improve. (Of course, I tended to focus on what hadn’t gone so well.)

This drive to keep improving came from a good place: a deep respect for the art of coaching, a commitment to my clients, and a desire to make their investment transformative. But before too long, this drive began to get in my way.

Ironically, my desire for perfection in coaching began to undermine my ability as a coach.

When I was focusing on my own performance, the coaching became all about me. When I was groping for the next powerful question, I wasn’t listening on a deep level. When I was busy batting away my inner critic, I wasn’t fully present to what was unfolding between my client and me: this human, vulnerable, creative conversation that neither one of us could predict, and that would never happen again.

It was then that I read something that genuinely revolutionised my approach to my performance.

I found it in Rob Bell’s book, How To Be Here: A Guide to Creating a Life Worth Living. A central focus of the book is the idea of craft. Bell argues that craft is inherent to each of us, and that we can cultivate it in how we live and work.

Here’s the passage that changed everything for me:

“There is a difference between craft and success.

Craft is when you have a profound sense of gratitude that you even get to do this.

Craft is when you relish the details.

Craft is your awareness that all the hours you’re putting in are adding up to something, that they’re producing in you skill and character and substance.

Craft is when you meet up with someone else who’s serious about her craft and you can talk for hours about the subtle nuances and acquired wisdom of the work.

Craft is when you realize that you’re building muscles and habits that are helping you do better what you do.

Craft is when you have a deep respect for the form and shape and content of what you’re doing.

Craft is when you see yourself part of a line of people who have done this particular work.

Craft is when you’re humbled because you know that no matter how many years you get to do this, there will always be room to learn and grow.

Success says, What more can I get?

Craft says, Can you believe I get to do this?”

— ROB BELL, HOW TO BE HERE: A GUIDE TO CREATING A LIFE WORTH LIVING

*

Seeing our work as craft is, in my mind, all about how we approach learning.

As leaders or entrepreneurs, we’re always needing to learn new things. We’re constantly challenged to grow, adapt, stretch, and expand our comfort zones, for the sake of the ideas and the people that we are responsible for. And so we’re always going to be exposing ourselves to getting it wrong. This can bring out the perfectionist big guns like nothing else: it feels like such an exposed way to risk failing.

And aside from our careers — as regular humans, we’re always learning and growing. Building a long-term relationship with someone. Raising children or caring for parents. Figuring out how to manage our finances. Looking after our mental health and physical fitness. Trying to live in accordance with our beliefs. Making changes that matter. There’s always the temptation to become fixated on achieving perfection.

A craft mindset can speak to all of these areas.

For me, three mantras have emerged out of this way of seeing:

“I’m not doing this alone.”

Self-doubt is deeply isolating. When we’re in the grip of perfectionism, we analyse our own abilities, critique our performance, and feel like we’re imposters just waiting to be found out. It’s all about us: focusing inwards. A craft mindset helps us remember that whatever our vocation — coaching, marketing, parenting, writing, consulting, data analysing, caring — we’re doing it within a community of other humans who are also learning, growing, making mistakes, doubting themselves, picking themselves up, and also making it up as they go, just like we are. The more we talk about our struggles and our questions, the more we realise that it’s not just us.

2. “We’re always apprentices.”

For me, the idea of craft reminds me of traditional trades — carpentry, ironmongery, masonry, sculpture — where skill progression would always begin with a multi-year apprenticeship: someone learning under the master, watching how they worked, letting themselves be taught. There was no shame in being an apprentice.

It’s much better to own that we don’t know it all than to pretend that we do — and so free up all that emotional energy to actually keep learning. There’s a freedom that comes from acknowledging we are still figuring stuff out — and to ask for help.

3. “Keep the bigger picture”.

It might feel like what just happened — whatever triggered our self-doubt and perfectionism — permanently defines our ability. But of course, it doesn’t. Conscious incompetence is one of the key stages of adult learning.

Let’s remember that none of us is a finished piece of work, and nor is our craft. What are we doing better now than we were twelve, six months ago? What’s going really well? Where do we already feel confident? And how much more skilled will we be twelve months from now? Five years from now? Ten? Twenty? How is what we’re going through now helping us hone our craft long-term?

Like an ironmonger hammering out a tool, or a sculpture chipping away at a bust, the ultimate shape of our craft is made slowly, through tiny and deliberate movements again and again and again. There’s no shortcut.

This trying and failing and trying and failing? This is the work.

Something to chew on: Where does perfectionism currently get out of hand for you? How might craft change that?

ThePowerMBA: Tools for Leadership, Sustainability and Innovation

I’m investing in my business education in 15 min/day. Perfect for a working parent! (4 min read)

Many opportunities have been popping up recently, and I’m sadly needing to say no to most of them. But recently, I’ve said yes to one: ThePowerMBA.

In this season of balancing work and parenthood, it can be challenging to know how to invest my time wisely. However, when I was invited to join the first global cohort of ThePowerMBA — the new ed tech making business education accessible and affordable to anyone who wants to learn — I decided to take the plunge. So: why this? And why now?

For most people who want a thorough grounding in business education, a traditional MBA is one of the options they look at. Without doubt, this can be a really valuable investment, especially if the school is well-connected. It can open lots of doors. But what if you don’t have two years of your life to commit to more education, or you’re unable to take out high levels of student debt?

ThePowerMBA was founded in order to democratise business education for anyone who wanted to thrive in business or entrepreneurship. It launched in Europe two years ago, and — 40,000 students later — is about to launch globally. As well as the thousands of students who are working through its program, many big brands (including Google, Microsoft, and Coca-Cola) are relying on it to teach their staff core business skills.

The curriculum consists of 250+ bite-sized (15-minute) lessons, which are drip-fed on weekdays over ten months. It’s delivered in part by the founders and executives of companies like Tesla, Air BnB, YouTube and Shazam, and complemented by local networking hubs run by Ambassadors.

Given my work with entrepreneurs and startups, I’ve been given the chance to enrol in ThePowerMBA, and to share what I’ll be learning as I go through the programme.

I believe this progamme will help me achieve three things:

1. It will deepen my understanding of effective, impactful leadership in business

ThePowerMBA curriculum is designed to provide a grounding in the core business tools – including strategy, business models, marketing, and finance – while also covering leadership and management. As such, it will widen my exposure to business case studies, and the impact of different leadership approaches.

I’m especially interested in hearing the personal stories of the founders and executives who are contributing to this programme. I’d like to learn more about how they approached problems, responded to challenges, and overcame obstacles on the way to business success (and — really importantly — their mindset in the volatile and fast-changing Coronavirus context).

I think there’s real potential for me to learn more about how to equip people with practical tools to solve social and environmental problems (see below), while meanwhile deepening my understanding of effective leadership in uncertain times. This, in turn, will help me speak to my clients’ leadership and personal development.

2. It will help me better serve people working to create big change

I believe that many of our toughest social and environmental problems can be solved through entrepreneurial thinking. However, often many of the people who are best placed to create change can lack a business background.

For example, for two years running, I’ve coached at The Journey: the world’s biggest climate innovation summer school, run by the EU. I worked with 80 smart and passionate twenty-somethings — most of them Master’s students — helping them think entrepreneurially in service of tackling climate change. I also co-designed and -coached the social innovation incubator, Good Ideas at The Melting Pot, for ambitious people who were committed to making social change but mostly lacked a business education.

In both these examples, we focused on adapting business tools to a social/environmental context: helping people verify that their service/product was actually wanted, and to design a financially sustainable business model.

It’s been so rewarding to have partnered with such creative, passionate, committed people, and to bear witness to the start-ups, social enterprises and non-profits that they’ve imagined and developed.

I already know and use a lot of the best design thinking tools out there, but there are definite gaps in my knowledge (especially around Finance and Marketing). I think that ThePowerMBA will broaden my education and teach me new tools and techniques. In turn, I’ll be better placed to help social innovators tackle the problems that keep them awake at night.

3. It feels like a workable way to commit to ongoing learning as a new parent

This one’s short, but important ☺

I haven’t switched off my love of learning just because my days now revolve around a little person. However, I’ve needed to switch up how I learn. I don’t have long chunks of time to devour a book in one sitting, and I’m not able to travel to all-day courses without childcare (especially in Corona times, with limited support).

However, 15 mins a day does feel doable. Over the course of ten months, ThePowerMBA amounts to 62 hours of learning. I can put our son to bed and watch a video with a glass of wine, or spend an hour at the weekend watching lessons I’ve missed. I know that for this to work for me in this busy season of life, it will need to be accessible, fun and sustainable.

To help me reflect on my main takeaways, I’ll be posting every month on this site once we kick things off in September 2020 Join me to find out what I’m learning!

How to Create a Values Compass

How can we use our values to navigate the chaos of transition? As a new mum, I’m learning this firsthand. (4 min read)

If you slice open a cocoon halfway through metamorphosis, you won’t find the caterpillar or the butterfly. Instead, you’ll find lots of … goop. The caterpillar digests itself, dissolving its organs into a soup, as a necessary part of the process of transformation. It’s messy, unformed, chaotic and creative.

The reality is that transition is often about flailing around in the goop before there’s anything to show for our efforts. When we’re in the middle of transition, we’re no longer our old selves — and we have no idea what or who we’re becoming. More than anything else, it’s often about just holding on and finding things that help in the meantime.

As a new mum, I’m smack bang in the middle of my own colossal transition. Four months ago — shortly before lockdown 2020 — my husband and I became parents. The last weeks have been a tumult of wonder, overwhelm, head-over-heels love, exhaustion and joy. Together, we’re navigating a ‘new normal’…that’s made even more abnormal by the backdrop of the pandemic and lockdown restrictions. Our lives were transformed at the same time that the wider world became unrecognisable.

And so in the midst of this, I’m figuring out what the ‘new me’ looks like. My work, my marriage, my sleep, my body and level of fitness, my emotional landscape, my free time, my relationships: everything has changed.

This means that I’ve been flailing around in a lot of goop. And as I’ve been doing so, I’ve been experimenting with certain practices that are helping me to find my feet. These practices are guiding me through the flux and the disorientation.

This particular practice is a Values Compass. Our values can be fantastic tools to help us navigate change (and life more broadly), so I love using them with clients. (I write about three specific ways they can help anchor us in this blog post.) The Values Compass is a tool you can create at home right now.

Creating a Values Compass in 4 Steps

1. Ask yourself: “Twenty years from now, what do I want to look back on about this period? What values do I want to have characterized how I lived?”

Jot these down as they come to you, and don’t worry about finding the ‘right’ answer (there isn’t one). If you end up brainstorming lots of values, just get them all down on paper. Then take time to winnow them down to just a handful — your key values for this season.

Alternatively, you may find that just one value emerges as your ‘north star’ right now. If that’s the case, don’t force yourself to find others. It’s likely that your intuition is telling you something important.

2. Now for each uncovered value, ask yourself: “What’s important about this to me?”

This step matters, because if the values don’t resonate with you – if there’s no energy in the value for you personally – you won’t be inspired by what you end up with, or motivated to pursue it. For example: the word ‘courage’ might mean very little to you – but ‘boldness’ or ‘daring’ or ‘bravery’ might.

In fact, you may not end up with a single word that describes your value. It might be a few words (‘seize the day’) or even a metaphor (‘gladiator’). What’s important is that it has a charge to it, deep down in your gut. You want it to feel like it’s you.

3. Create a simple visual of your values

Once you’ve solidified the values that most speak to you, write them on a post-it note and stick it to your mirror. Find a picture online that captures their essence, and save it as your desktop background. On a blank piece of paper, depict them in symbols, shapes or colours (a wheel? a diagram? a coat of arms?) and put it somewhere you’ll see it.

Why? It helps cement and deepen the values in your mind, and of course makes it more likely you'll see them regularly. In turn, this increases their potential to influence you, inspire you, and help guide your choices during the day.

4. Experiment with intentional practice

Now comes the part that actually brings this home. For a period of time – perhaps a day or a week – choose one of the values from your compass. During that time, experiment with different ways of honouring that value.

Notice the forks in the road where you can tap into this value to help govern decisions. Notice activities that help this value come alive. Observe what happens as you try out different things, and how you feel as you do so. What do you learn? What works well? How does practising this value impact your experience of this transition?

The next day or week, choose a different value and do the same thing. The aim here is to find small ways of incorporating what’s most important to you, so that – over time – you can start forming patterns that are in line with your priorities. (You might want to try immediately honouring all the values all the time, and of course you can try — but it might be counterproductive. Transitions can already feel exhausting without trying to initiate something huge all at once, and these kinds of changes are less likely to last.)

This is all about making small, curious steps towards change, so that you can experiment with different ways of journeying through this transition in ways that feel like you. Your values compass is a tool to help you navigate a season that can feel confusing, out of control, and disorienting.

Take it at the pace that’s right for you, and keep on experimenting and exploring, following your own compass to guide you through this transition and out the other side: more self-aware, resilient, and purposeful.

Something to chew on: Which value do you feel most drawn to exploring at the moment? What small step can you take to bring more of that into your life this week?

Anchoring Yourself in Times of Change

In times of transition, what is it about knowing our values that can be so helpful? (3 min read)

Knowing what’s most important to us is a colossal help in times of personal transition: those times in our lives and careers when so much is up in the air, a lot feels out of our control, and we’re struggling to stay afloat. They can also really help in times of wider societal change — like the pandemic — when our sense of helplessness can be exacerbated. So what makes knowing our values so helpful in times of change?

Values are the foundation of much of my coaching work: I spend 90 minutes, at the start of many new coaching relationships, digging deep into what’s most important to my clients. Once they’ve unpacked and clarified their values, they can go back to them when they need to make tough decisions, handle conflict, discern the way forward, or do a personal check-in.

(I show you how to create your own Values Compass — a much-simplified version of this work — here.)

So: when we’re going through change, what’s so helpful about knowing our values?

1. Our values give us a sense of agency and purpose.

When we’re in transition, so much feels outside of our control. Focusing on our values reminds us that – while we may not be able to control our circumstances – we can choose how we respond.

We always have a choice.

Victor Frankl, the Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, writes about this brilliantly in his incomparable memoir Man’s Search for Meaning (1946). In it, he writes of his experience in Auschwitz, witnessing and wrestling with indescribable horror and death. He noticed that the inmates who were most resilient were those who still managed to exercise choice in the face of such devastation. He writes:

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

For Frankl, we humans are meaning-making creatures. Without meaning, we lose hope. Knowing our values helps us to make choices that align with who we are, and help us shape purpose-driven lives.

2. Our values help us retain a consistent thread of identity.

This is particularly important in times of change, which can sometimes threaten our sense of self. Starting a new job or company, being laid off or furloughed, retiring, graduating, marrying or divorcing, becoming a parent, having our kids leave home, moving across the country — these are all massive interruptions to the pattern of how we show up in the world and perceive ourselves.

However, our values are deeply personal. While they may evolve over time, as we grow and change, they don’t tend to alter unrecognisably. Getting clear about our values reminds us that there is, in fact, a commonality between the self before this transition and the self during it. We’re still ourselves, and we’ll still be ourselves in whatever comes next, perhaps deepened or expanded or matured.

3. Our values let us regain perspective.

Often our values become apparent when we step back from a situation and its emotional charge. When we take the helicopter view, we’re better able to situate the current transition within the context of the rest of our life. We remember all the other transitions that have made us who we are. We stick our head up above the trenches for a moment, and – with this new perspective – are better able to see what’s most important to us.

That’s why the first step in creating a Values Compass is to take a twenty-year perspective. When this transition is over and we’re looking back from the year 2040, what’s going to have mattered most to us? And how are we going to have lived this out?

Something to chew on: Which of these elements — your agency, your identity, or a sense of perspective — is most helpful to you right now in the transition you’re going through?